El Greco: Out of Time

- Art Trading & Finance

- Jul 1, 2025

- 5 min read

Exploring the timeless genius of El Greco’s visionary style

El Greco, born Doménikos Theotokópoulos in 1541 on the island of Crete, stands as one of the most enigmatic and visionary figures in Western art. Bridging the divide between ancient Byzantine traditions and the radical innovations of the Renaissance, El Greco carved a path that left him unclassifiable by contemporary standards — and virtually unplaceable within conventional art history narratives. In many ways, El Greco out of time is not just a statement of style, but a lens through which to understand his unique and prophetic legacy.

El Greco out of time: From Crete to the Renaissance heartlands

Crete in the 16th century was a Venetian outpost, and El Greco was initially trained as an icon painter in the rigid, symbolic world of Byzantine religious art. Yet, even early on, his work displayed a desire to break from traditional iconography, hinting at an artist restless to explore new dimensions.

In 1567, seeking broader artistic horizons, he moved to Venice, the beating heart of the Italian Renaissance. Here, he encountered the masterpieces of Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto. From these luminaries, he absorbed the Venetian passion for color, drama, and movement — all elements that would remain central to his work throughout his life. His exposure to the Venetian school shaped not just his technical abilities but his philosophical outlook on art as a spiritual and intellectual pursuit.

By 1570, El Greco had relocated to Rome, the epicenter of classical tradition and artistic patronage. He studied ancient sculptures and the mathematical proportions of Michelangelo’s figures while simultaneously engaging with the expressive elongation found in Mannerist artists like Parmigianino. The influence of this Italian period culminates in works like Christ Driving the Money Changers from the Temple (ca. 1570), in which we see the full force of Venetian lighting, dynamic gestures, and Renaissance composition—all charged with religious symbolism.

The story of Jesus expelling the moneylenders became a favored theme during the Counter-Reformation, used to represent moral purification within the Catholic Church. El Greco’s interpretation aligned with this spirit while injecting it with unprecedented intensity.

Despite his technical brilliance and original vision, El Greco faced rejection from the Roman establishment. He failed to secure major commissions, partly due to his bold reinterpretations and unconventional style, which seemed too eccentric for conservative tastes. His suggestion that Michelangelo “did not know how to paint” did little to help his standing.

Toledo: A sanctuary for artistic freedom

In 1576, El Greco departed Italy for Toledo, Spain, where his true artistic identity would flourish. Toledo was then a major religious and intellectual hub, steeped in mysticism and theological debate. There, he found a more receptive audience in a community of thinkers, theologians, and reform-minded clergy who appreciated the emotional and spiritual resonance of his art.

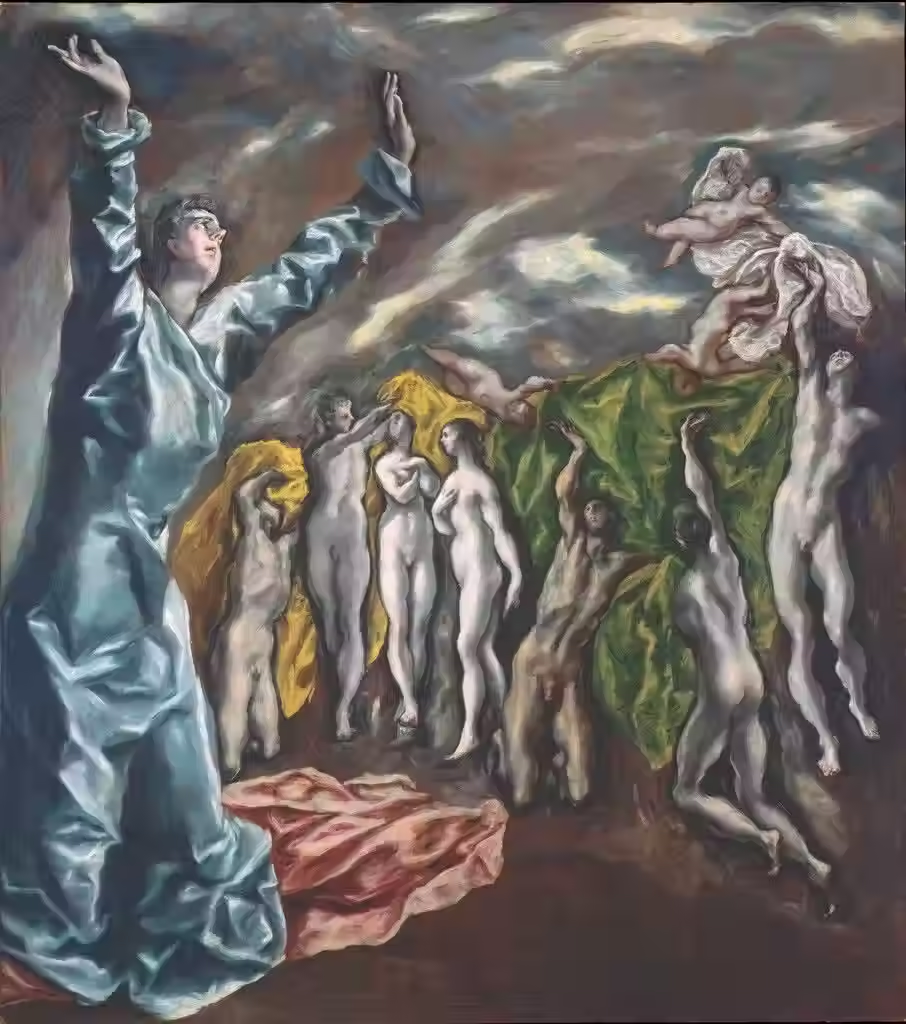

El Greco’s first major Spanish commission was the Assumption of the Virgin (1577–79), a large altarpiece for the Church of Santo Domingo el Antiguo. The work immediately demonstrated his matured style: elongated figures, swirling skies, glowing colors, and intense spirituality. His signature approach — combining Byzantine abstraction with Venetian sensuality and Mannerist elongation — had finally found a stage worthy of its power.

In Toledo, El Greco did not simply paint religious subjects — he spiritualized them. His figures do not inhabit physical space so much as they ascend through it, transcending earthly limits.

He quickly became the city’s leading artist and established a busy workshop, producing altarpieces, portraits, and devotional works. Although he trained assistants, El Greco’s singular vision meant that no real "school" of followers emerged, and his art remained deeply personal.

One of his few non-religious works from this period is A View of Toledo (1599–1600), considered by many to be the first true expressionist landscape in Western painting. Its stormy sky, unnatural lighting, and emotionally charged atmosphere mark a stark departure from the serene, idealized nature of Renaissance landscapes.

This painting anticipated the modernist emotional landscape of Van Gogh and the symbolic abstraction of Edvard Munch centuries before they arrived on the scene.

A misunderstood genius who inspired modern masters

Despite his growing reputation in Toledo, El Greco remained marginalized by mainstream Spanish art circles, which favored the restrained classicism of the Spanish Renaissance. His spiritual fervor, unconventional figures, and lack of adherence to naturalism puzzled critics and patrons alike.

It wasn’t until the 19th-century Romantic revival that El Greco’s art found new life. Romantic painters admired his wild brushwork, intense emotion, and artistic independence. Later, the early 20th-century modernists, especially in France and Spain, would claim him as one of their own.

· Vincent van Gogh saw in El Greco’s skies and sacred figures the same ecstasy he sought

in his own work.

· Pablo Picasso, who called him “a Venetian painter… but Cubist in construction,” was

profoundly influenced by El Greco’s distorted anatomy and structural abstraction.

· Paul Cézanne, Egon Schiele, and Paul Gauguin each found elements of their own avant-

garde styles prefigured in El Greco’s vision.

For many art historians today, El Greco’s legacy is not simply as a precursor to Baroque or Expressionism, but as a perennial outlier — a figure whose art refuses to be boxed into any one moment or movement.

For more on this artistic evolution, the Metropolitan Museum of Art offers a comprehensive timeline linking El Greco to the broader context of European art.

A legacy beyond classification

El Greco’s work occupies a unique space between tradition and transformation. His use of spiritual symbolism, exaggerated form, vibrant color, and ecstatic light continues to captivate audiences around the world. He painted saints, martyrs, apostles, and visions of the heavens with the same intensity and fervor that modern artists would later apply to their inner emotional landscapes.

Most tellingly, El Greco never adopted a Spanish or Italian version of his name. He signed his paintings using his Greek name, Doménikos Theotokópoulos, in Greek script — a powerful assertion of identity that emphasized his cultural and creative independence.

His art lives outside of time because El Greco himself stood outside of convention.

Dive deeper into timeless genius

If the story of El Greco out of time has captivated you, you're not alone. His life and legacy invite reflection on how great art defies easy categorization. At AR Trading Finance, we explore such cultural intersections and offer unique insights into art, history, and travel. Don’t miss out — subscribe to our newsletter for updates on exclusive offers, cultural content, and investment tips.

Want more stories like this? Visit our blog for in-depth articles on European art, historical destinations, and the hidden corners of the British Virgin Islands. Follow us on social media to stay inspired every day.

Comments